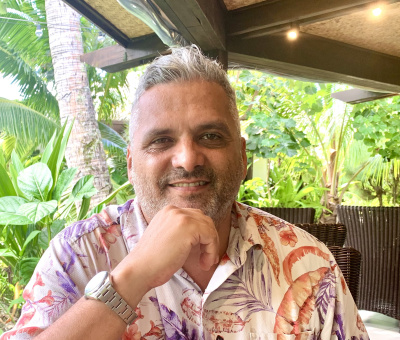

When Gerald McCormack came to the Cook Islands in 1980 as the government's schools science advisor, he was surprised students were not being taught about local plants and animals. Teachers knew Maori names, but rarely English or Latin names - and neither did Gerald!

“Someone had to start recording the plants and animals with their Maori, English and latin names - a good challenge for a new science advisor.”

Gerald has been the lead researcher since then and continues to contribute to the Cook Islands Biodiversity Database: “Nowadays the database contains around 4500 plants and animals, including fish”.

We asked Gerald what plants and animals a visitor might typically encounter.

“Most will encounter the House Gecko. It’s a new gecko that arrived around 1990 and spread quickly. It is a loud gecko. Most geckos make little noise. This one is almost like a chirping bird.

“Most will encounter the House Gecko. It’s a new gecko that arrived around 1990 and spread quickly. It is a loud gecko. Most geckos make little noise. This one is almost like a chirping bird.

“None of the geckos or skinks found in the Cook Islands is indigenous”.

Gerald pointed out that the Cook Islands do not have native mammals either, except for the fruit bat, which was originally native on Mangaia and has since spread: “Only people wandering up valleys in the evening will encounter a fruit bat or if you go to the Takituma Conservation Area on a nature walk with a guide.

“By far the most common animal encountered by visitors is the dog: “Europeans introduced dogs, though there was once a Polynesian dog. About 1000 years ago the Polynesians brought chickens, dogs, pigs and the Pacific rat – they bought them all mainly as food.

“By far the most common animal encountered by visitors is the dog: “Europeans introduced dogs, though there was once a Polynesian dog. About 1000 years ago the Polynesians brought chickens, dogs, pigs and the Pacific rat – they bought them all mainly as food.

“The Polynesian dog was a very different looking dog. It was a small dog with up pointing ears, and it was barkless. The strangest thing about it was its outturned front feet. Today you see many dogs with outturned front feet – the question is whether this in fact indicates that some of the genetic material from those early dogs survived, or does this feature come from dogs more recently, possibly a dog like a corgi?

“The Polynesian dog died out fairly quickly, the people lost interest in it when they saw the bigger dogs coming in with the European settlers; as they did with the pigs too!”

Some of the Cook Islands that have no dogs, including Aitutaki.

“There are many colourful stories as to why there are no dogs on Aitutaki including the possibility that in the days of leprosy (1880s-1920s) it was thought that dogs spread the disease. Whichever is correct, Aitutaki has been clear of dogs since the early 1900s”.

What will visitors come across in the lagoons and on the beaches?

“The Pacific Reef Heron on the beach, on a rock, or in the shallow water. It can be white or speckled. They are very shy and stay away from people.

“The Pacific Reef Heron on the beach, on a rock, or in the shallow water. It can be white or speckled. They are very shy and stay away from people.

“Another one visitors will see is one that runs ahead of you on the beach, the sandpiper. It is actually the Wandering Tattler. It stays around the waters edge looking for its food. If you walk behind it long enough it will fly around you and land behind you. At the same time it gives a characteristic call and the local name for that is Kuriri – after the sound it makes. It is highly territorial bird.”

What about in the lagoon itself?

“The most common creature everybody sees is the black sea cucumber. There is lots of sediment and organic matter in the lagoon and the sea cucumber is like a vacuum cleaner that sucks up the sand and poops it out cleaned.”

“The most common creature everybody sees is the black sea cucumber. There is lots of sediment and organic matter in the lagoon and the sea cucumber is like a vacuum cleaner that sucks up the sand and poops it out cleaned.”

Gerald reminds visitors there are number of ways they can easily injure themselves in the lagoon: “You shouldn’t be touching anything in the water!”

“Grabbing hold of a rock or coral that is sharp. You certainly don’t put your hand in any hole – that is just asking a moray to take a finger. The only thing that people really worry about is the stonefish, though they’re not that common here. The thing that is common here is the scorpion fish – and it is nowhere near as dangerous as a stonefish. Neither of them dig in to the sand, they lie on top of it. They are an ambush predator. They lie disguised on the sand or near coral waiting for a little fish to go over the top; then they just leap up and suck it in.

“They don’t attack people; people attack them. If it doesn’t think it has time to move, it raises its spines, and you are going to inject yourself with a poison. The treatment is very simple, just use non-scalding hot water.”

“When you go snorkeling you are going to see a whole variety of fish. The convict tang (aka surgeon fish) is a dramatic little fish often in big schools. You’ll see lots of goatfish and parrot fish too”.

“When you go snorkeling you are going to see a whole variety of fish. The convict tang (aka surgeon fish) is a dramatic little fish often in big schools. You’ll see lots of goatfish and parrot fish too”.

What about the turtle?

“We have hawksbill turtles and green turtles. Hawksbill turtles are non-migratory wandering turtles; it is not easy to predict where they are going to be. The green turtle is a traditional turtle that does not normally breed in the Cook Islands. They breed mainly in Fiji and Vanuatu then swim to the Cook Islands. They’re seen regularly in the lagoon on Aitutaki, and more and more around Rarotonga”.

What about the most common trees seen in the islands?

“On the lowland, the flamboyant is the most spectacular tree from November through the summer, aka the flame tree. You can easily recognise its umbrella –type appearance. Another beautiful tree is the golden shower – incredible bundles of yellow flowers hanging off these trees”.

“They can be almost any colour! It is an interesting plant. Here in Rarotonga we have the hibiscus that was originally introduced by the Polynesians. When you do the cross-island walk you will see the hibiscus shrubs there; the flowers on those shrubs is a dark red with multiple petals. Red is the colour of chiefs. There is a smaller hibiscus on the lowlands, which you often see in hedges, that too was introduced by the Polynesians”.

Gerald has also been recording medicinal plants since he came here in 1981. On the database they record 160 plants listed as having some sort of medicinal use. More than half the plants listed have come since the missionaries in the 1800s.

He tells the story of one of the famous cases of medicinal plants in the Cook Islands - the source of Mauke Miracle Oil discovered by a fourteen-year old girl in the late 1970s.

“By the time I came to the Cooks, everyone seemed to have a bottle, putting in on every little sore they had and so on. And, they were all saying this was miracle oil!,” said Gerald.

“The story behind miracle oil was that this fourteen year old girl had a dream that a woman dressed in white came to her and took her to a place on the island, which was well described in the dream, which showed her a plant which was used to make an oil. When she woke up she told her mother about the dream. Now her mother was a famous medicinal person on the island on Mauke, and also a royal person. She said that is the ‘medicine for the man’. The night before, her father had said he knew of a man that was extremely ill in hospital. He had put a fork through his foot and the medicines from the hospital were not working. The mother made the oil according to the dream and they gave it to this man and within no time at all he was cured of his infection. So he said it was a miracle – hence miracle oil was born! Now known commercially as Mauke Miracle Oil.

“Other medicines are family traditions, so they are not available commercially; they’re part of the social structure of the islands.”

Whilst it is known there was a native coconut palm here before Polynesian habitation, they brought with them the coconut trees we see most abundantly today. The native one was smaller.

Whilst it is known there was a native coconut palm here before Polynesian habitation, they brought with them the coconut trees we see most abundantly today. The native one was smaller.

“The variety the Polynesians brought had bigger nuts because they contained more juice and more flesh. Coconut trees last only up to a hundred years, so when the native coconut tree was replaced by the version brought by the Polynesians it didn’t take long to die out”.

The productive coconut palm is considered by Cook Islanders as the ‘tree of life’. They could not imagine living without it!

Gerald McCormack is Director of the Cook Islands Natural Heritage Trust. He has worked with the Cook Islands Government since 1980 as Science Advisor to the Ministry of Education, Director of the Conservation Service, and Director of the Natural Heritage Project. Gerald has a First Class Masters in Zoology, and is an accomplished photographer and author. He is also President of the Cook Islands Library Museum Society Council.